Scrappy freelance work on location in Vietnam, Costa Rica, Spain and Buffalo in the 1990s. Seasoned studio executive jobs in Jordan, Germany and New York City in the 2000s. Gretchen McGowan recounts it all in her provocative new book Flying ...

“Last Comiskey” represents a mutual love letter to the final Major League Baseball season at Chicago’s Old Comiskey Park. The passion project began with a documentary by Matt Flesch, soon to be accompanied by Ken Smoller’s book. Last Comiskey’s Photos ...

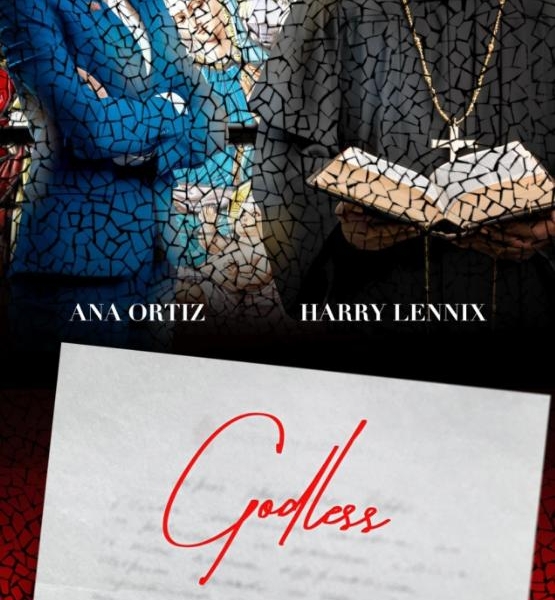

“Godless” is a new faith-based political drama from director and co-writer Michael Ricigliano. When politics and the Catholic Church collide can there be a meeting of the minds? And souls? No issue off limits. Ricigliano doesn’t shy away from hotly ...

We love that many of our remarkable readers will ask, “Hey, why not that 1980s film?” Or “Where is this ‘80s flick?” This means it matters. And, after all, isn’t that the point, fine friends of TMB Here now, seven ...

Internet personality Jennifer Murphy went viral in the summer of 2016 with her song “I Want to Be Neenja”. The quirky sendup reportedly topped 1 billion online views worldwide, and over 88 million hashtags on TikTok. The runaway success of ...

“Betrayed” draws from the true story of the Norwegian boxer Charles Braude and his family, who were persecuted, arrested, and murdered by the Nazis during World War II. Appallingly, the entire process was carried out with the full participation of ...

Two young women take a trip to New York. Or do they? Something happened at 625 River Road. Whatever it was remains a disturbing mystery. Promising Debut The horror thriller “What Happened at 625 River Rd” is the first feature ...

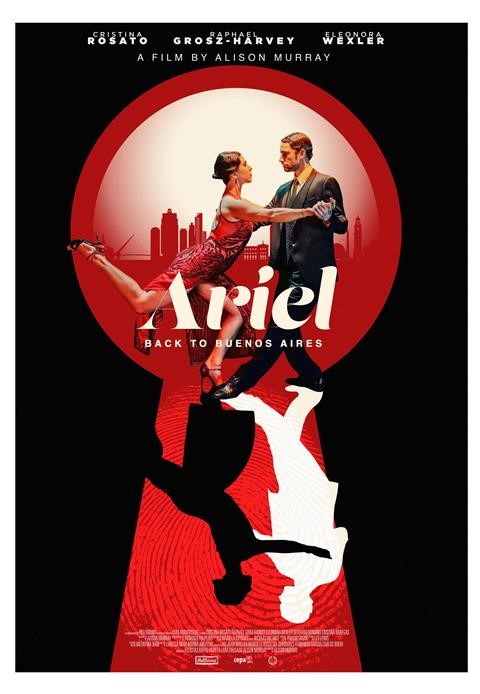

“Ariel: Back to Buenos Aries” is a captivating story of a brother and sister returning to their birthplace, Argentina, for the first time as adults. Soon immersed in the glimmering tango clubs of Buenos Aires, they come to uncover long-kept ...

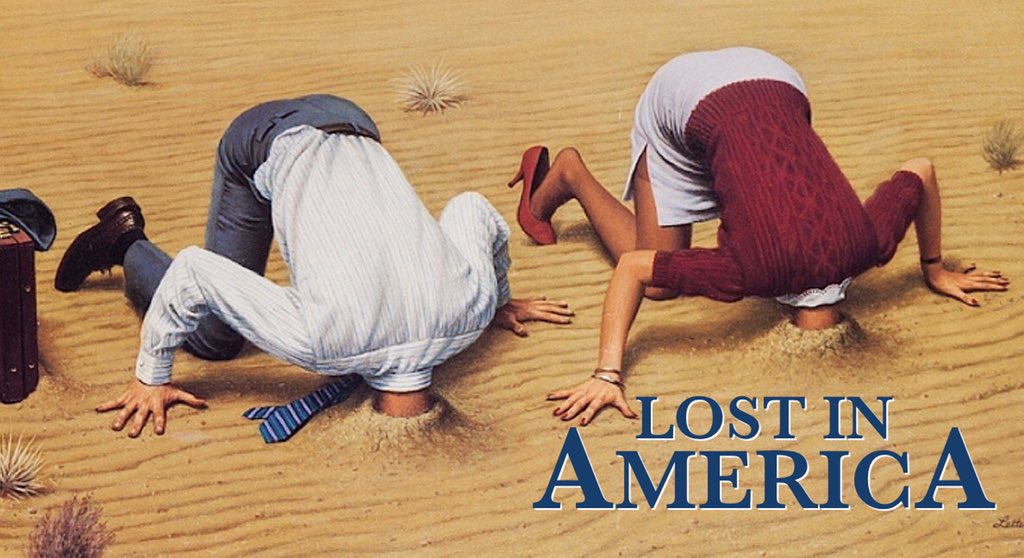

Two yuppies decide to “drop out of society” and hit the road in a motorhome to do all the things they dreamed about in their youth. Albert Brooks (“Broadcast News”, “Defending Your Life”) directs and stars as a hot shot ...

This “Christine” review tells the tragic true story of Christine Chubbuck, a 1970s local TV news reporter. Chubbuck struggled mightily with depression and professional frustrations while striving to advance in her career. “Christine” Review (2016): Riveting Chronicle of Ravaging Mental ...

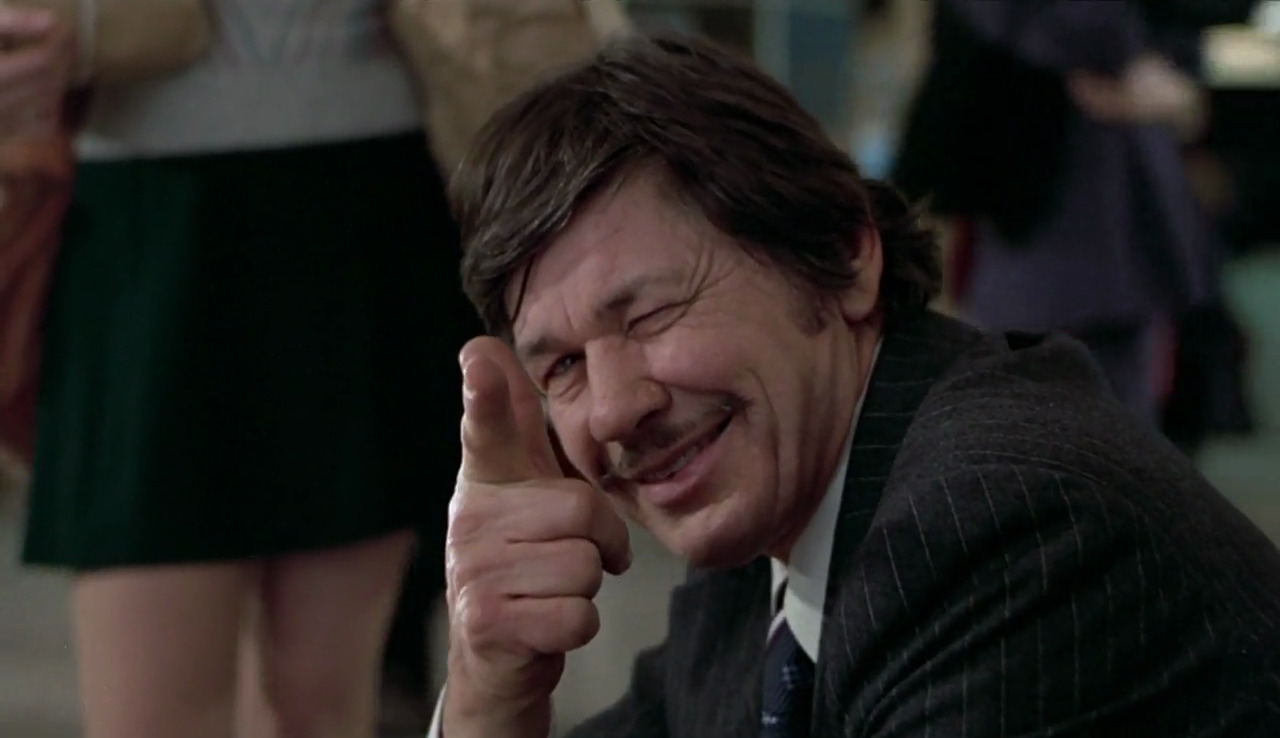

“Death Wish” tells the story of New York City architect Paul Kersey, who becomes a one-man vigilante squad after his wife is senselessly slain by street thugs. In self-defense, the vengeful man commences killing muggers on the mean streets after ...

Coal Miner’s Daughter is the rags-to-riches story of legendary country music singer Loretta Lynn. The film covers the Kentucky native’s early teen years in a poor family, getting married at 15, and her rise to become one of the most ...